Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is a hip condition that occurs in teens and pre-teens who are still growing. For reasons that are not well understood, the ball at the head of the femur (thighbone) slips off the neck of the bone in a backwards direction. This causes pain, stiffness, and instability in the affected hip. The condition usually develops gradually over time and is more common in boys than girls.

Treatment for SCFE involves surgery to stop the head of the femur from slipping any further. To achieve the best outcome, it is important to be diagnosed as quickly as possible. Without early detection and proper treatment, SCFE can lead to potentially serious complications, including painful arthritis in the hip joint.

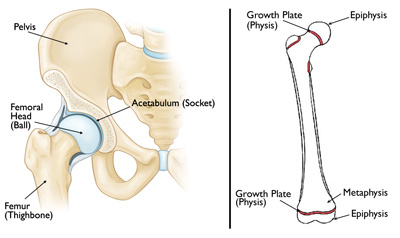

AnatomyThe hip is a ball-and-socket joint. The socket is formed by the acetabulum, which is part of the large pelvis bone. The ball is the femoral head, which is the upper end of the femur (thighbone).

Like the other long bones in the body, the femur does not grow from the center outward. Instead, growth occurs at each end of the bone around an area of developing cartilage called the growth plate (physis).

Growth plates are located between the widened part of the shaft of the bone (metaphysis) and the end of the bone (epiphysis). The epiphysis at the upper end of the femur is the growth center that eventually becomes the femoral head.

(Left) Normal anatomy of the hip. (Right) The location of the growth plates and epiphyses at the ends of the femur (thighbone). The epiphysis at the upper end of the bone eventually becomes the femoral head.

Description

(Left) Normal anatomy of the hip. (Right) The location of the growth plates and epiphyses at the ends of the femur (thighbone). The epiphysis at the upper end of the bone eventually becomes the femoral head.

Description

SCFE is the most common hip disorder in adolescents. In SCFE, the epiphysis, or head of the femur (thighbone), slips down and backwards off the neck of the bone at the growth plate, the weaker area of bone that has not yet developed.

An illustration of SCFE. The femoral head has shifted slightly downward off the neck of the bone through the growth plate (arrow).

Courtesy of John Killian, MD, Birmingham, AL

An illustration of SCFE. The femoral head has shifted slightly downward off the neck of the bone through the growth plate (arrow).

Courtesy of John Killian, MD, Birmingham, AL

SCFE usually develops during periods of rapid growth, shortly after the onset of puberty. In boys, this most commonly occurs between the ages of 12 and 16; in girls, between the ages of 10 and 14.

Sometimes SCFE occurs suddenly after a minor fall or trauma. More often, however, the condition develops gradually over several weeks or months, with no previous injury.

SCFE is often described based on whether the patient is able to bear weight on the affected hip. Knowing the type of SCFE will help your doctor determine treatment.

Types of SCFE include:

- Stable SCFE. In stable SCFE, the patient is able to walk or bear weight on the affected hip, either with or without crutches. Most cases of SCFE are stable slips.

- Unstable SCFE. This is a more severe slip. The patient cannot walk or bear weight, even with crutches. Unstable SCFE requires urgent treatment. Complications associated with SCFE are much more common in patients with unstable slips.

SCFE usually occurs on only one side; however, in up to 40 percent of patients (particularly those younger than age 10) SCFE will occur on the opposite side, as well—usually within 18 months.

CauseThe cause of SCFE is not known. The condition is more likely to occur during a growth spurt and is more common in boys than girls.

Risk factors that make someone more likely to develop the condition include:

- Excessive weight or obesity—most patients are above the 95th percentile for weight

- Family history of SCFE

- An endocrine or metabolic disorder, such as hyperthyroidism—this is more likely to be a factor for patients who are older or younger than the typical age range for SCFE (10 to 16 years of age)

An 11-year-old boy with unstable SCFE. His affected leg is turned outward and is shorter than the other leg.

Reproduced from Weber MD, Naujoks R, Smith BG: Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Orthopaedic Knowledge Online Journal 2008; 6(2). Accessed June 2016.

An 11-year-old boy with unstable SCFE. His affected leg is turned outward and is shorter than the other leg.

Reproduced from Weber MD, Naujoks R, Smith BG: Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Orthopaedic Knowledge Online Journal 2008; 6(2). Accessed June 2016.

Symptoms of SCFE vary, depending upon the severity of the condition.

A patient with mild or stable SCFE will usually have intermittent pain in the groin, hip, knee and/or thigh for several weeks or months. This pain usually worsens with activity. The patient may walk or run with a limp after a period of activity.

In more severe or unstable SCFE, symptoms may include:

- Sudden onset of pain, often after a fall or injury

- Inability to walk or bear weight on the affected leg

- Outward turning (external rotation) of the affected leg

- Discrepancy in leg length—the affected leg may appear shorter than the opposite leg

Physical Examination

Your doctor will check range of motion in the affected hip.

Reproduced from Weber MD, Naujoks R, Smith BG: Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Orthopaedic Knowledge Online Journal 2008; 6(2). Accessed June 2016.

Your doctor will check range of motion in the affected hip.

Reproduced from Weber MD, Naujoks R, Smith BG: Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Orthopaedic Knowledge Online Journal 2008; 6(2). Accessed June 2016.

During the examination, your doctor will ask about your child's general health and medical history. He or she will then talk with you about your child's symptoms and ask when the symptoms began.

While your child is lying down, the doctor will perform a careful examination of the affected hip and leg, looking for:

- Pain with extremes of motion

- Limited range of motion in the hip--especially limited internal rotation

- Involuntary muscle guarding and muscle spasms

Your doctor will also observe your child's gait (the way he or she walks). A child with SCFE may limp or have an abnormal gait.

X-rays

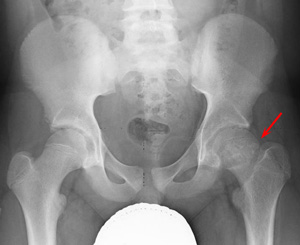

This type of study provides images of dense structures, such as bone. Your doctor will order x-rays of the pelvis, hip, and thigh from several different angles to help confirm the diagnosis.

In a patient with SCFE, an x-ray will show that the head of the thighbone appears to be slipping off the neck of the bone.

X-ray of a 12-year-old boy with stable SCFE in his left hip (arrow).

Reproduced from Weber MD, Naujoks R, Smith BG: Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Orthopaedic Knowledge Online Journal 2008; 6(2). Accessed June 2016.

Treatment

X-ray of a 12-year-old boy with stable SCFE in his left hip (arrow).

Reproduced from Weber MD, Naujoks R, Smith BG: Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Orthopaedic Knowledge Online Journal 2008; 6(2). Accessed June 2016.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to prevent the mildly displaced femoral head from slipping any further. This is always accomplished through surgery.

Early diagnosis of SCFE provides the best chance of stabilizing the hip and avoiding complications. When treated early and appropriately, long-term hip function can be expected to be very good.

Once SCFE is confirmed, your child will not be allowed to bear weight on his or her hip and will probably be admitted to the hospital. In most cases, surgery is performed within 24 to 48 hours.

Procedures

The surgical procedure your doctor recommends will depend upon the severity of the slip. Procedures used to treat SCFE include:

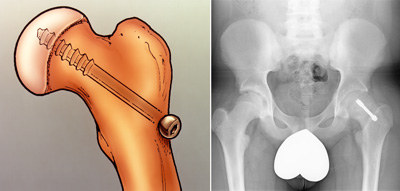

In situ fixation. This is the procedure used most often for patients with stable or mild SCFE. The doctor makes a small incision near the hip, then inserts a metal screw across the growth plate to maintain the position of the femoral head and prevent any further slippage.

Over time, the growth plate will close, or fuse. Once the growth plate is closed, no further slippage can occur.

Illustration and x-ray of in situ fixation. A single screw is inserted to prevent any further slip of the femoral head through the growth plate.

(Left) Courtesy of John Killian, MD, Birmingham, AL. (Right) Reproduced from Weber MD, Naujoks R, Smith BG: Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Orthopaedic Knowledge Online Journal 2008; 6(2). Accessed June 2016.

Illustration and x-ray of in situ fixation. A single screw is inserted to prevent any further slip of the femoral head through the growth plate.

(Left) Courtesy of John Killian, MD, Birmingham, AL. (Right) Reproduced from Weber MD, Naujoks R, Smith BG: Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Orthopaedic Knowledge Online Journal 2008; 6(2). Accessed June 2016.

Open reduction. In patients with unstable SCFE, the doctor may first make an open incision in the hip, then gently manipulate (reduce) the head of the femur back into its normal anatomic position.

The doctor will then insert one or two metal screws to hold the bone in place until the growth plate closes. This is a more extensive procedure and requires a longer recovery time.

(Left) X-ray of a 12-year-old boy with unstable SCFE (arrow). (Right) The femoral head has been manipulated (reduced) back into place and two screws have been inserted to hold it in place.

Reproduced from Weber MD, Naujoks R, Smith B: Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Orthopaedic Knowledge Online Journal 2008; 6(2). Accessed June 2016.

(Left) X-ray of a 12-year-old boy with unstable SCFE (arrow). (Right) The femoral head has been manipulated (reduced) back into place and two screws have been inserted to hold it in place.

Reproduced from Weber MD, Naujoks R, Smith B: Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Orthopaedic Knowledge Online Journal 2008; 6(2). Accessed June 2016.

In situ fixation in the opposite hip. Some patients are at higher risk for SCFE occurring on the opposite side. If this is the case with your child, your doctor may recommend inserting a screw into his or her unaffected hip at the same time to reduce the risk of SCFE. Your doctor will talk with you about whether this is appropriate for your child.

In this x-ray, two screws have been inserted in the patient's right hip to stop progression of a slip. A single screw has been inserted in the left hip to prevent SCFE from developing.

Reproduced from Woiczik MR, Pizzutillo PD, Gross RH, Carroll KL: Musculoskeletal effects of Down Syndrome. Orthopaedic Knowledge Online Journal 2012; 10(10). Accessed June 2016.

Complications

In this x-ray, two screws have been inserted in the patient's right hip to stop progression of a slip. A single screw has been inserted in the left hip to prevent SCFE from developing.

Reproduced from Woiczik MR, Pizzutillo PD, Gross RH, Carroll KL: Musculoskeletal effects of Down Syndrome. Orthopaedic Knowledge Online Journal 2012; 10(10). Accessed June 2016.

Complications

Although early detection and proper treatment of SCFE will help decrease the chance of complications, some patients will still experience problems.

The most common complications following SCFE are avascular necrosis and chondrolysis.

Avascular Necrosis

If severe cases, SCFE causes the blood supply to the femoral head to become limited. This can lead to a gradual and very painful collapse of the bone—a condition called avascular necrosis (AVN) or osteonecrosis.

When the bone collapses, the articular cartilage covering the bone also collapses. Without this smooth cartilage, bone rubs against bone, leading to painful arthritis in the joint. For some patients with AVN, further surgery may be needed to reconstruct the hip.

AVN is more likely to occur in patients with unstable SCFE. Because evidence of AVN may not be seen on x-ray for up to 12 months following surgery, the patient will be monitored with x-rays during this period of time.

Chondrolysis

Chondrolysis is a rare but serious complication of SCFE. In chondrolysis, the articular cartilage on the surface of the hip joint degenerates very rapidly, leading to pain, deformity, and permanent loss of motion in the affected hip.

Although the cause of the condition is not yet fully understood by doctors, it is believed that it may result from inflammation in the hip joint.

Aggressive physical therapy and anti-inflammatory medications may be prescribed for patients who develop chondrolysis. Over time, there may be some gradual return of motion in the hip.

RecoveryWeight Bearing

After surgery, your child will be on crutches for several weeks. The doctor will give you specific instructions about when full weight bearing can begin. To prevent further injury, it is important to closely follow your doctor's instructions.

Physical Therapy

A physical therapist will provide specific exercises to help strengthen the hip and leg muscles and improve range of motion.

Sports and Other Activities

For a period of time after surgery, your child will be restricted from participating in vigorous sports and activities. This will help minimize the chance of complications and enable healing to take place. Your doctor will tell you when your child can safely resume his or her normal activities.

Follow-Up Care

Your child will return to the doctor for follow-up visits for 18 to 24 months after surgery. These visits may include x-rays every 3 to 4 months to ensure that the growth plate has closed and that no complications have developed.

Depending upon the patient's age and other factors, a team approach that includes a general pediatrician, endocrinologist, and/or dietician may be necessary for comprehensive care in the long run.

For More InformationIf you found this article helpful, you may also be interested in The Impact of Childhood Obesity on Bone, Joint, and Muscle Health.

Source: http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=A00052